Two Sides of the Fantasy Coin

Let me be honest. I didn’t set out to write a story that fit neatly into one genre. I grew up reading Tolkien and watching anime, flipping between Brandon Sanderson paperbacks and martial arts and reincarnation manhwa.

Somewhere along the way, I started asking myself: what if we could have both? This blog post is me answering that question, not just as a fantasy author but as a lifelong fan who sees the world of fantasy evolving in real time. From the sweeping kingdoms of Western high fantasy to the mist-shrouded peaks of Eastern cultivation stories, readers today aren’t choosing sides. They want it all. And if you’re here, maybe you do too.

So let’s dive in—not just into the differences between Eastern and Western fantasy, but into what modern readers actually crave, and how hybrid stories might be the key to giving them something that feels both familiar and new.

The Core Differences Between Eastern vs Western Fantasy

Eastern Fantasy: This umbrella term includes subgenres like wuxia (martial hero tales), xianxia (immortal cultivation epics), and xuanhuan (mystical fantasy with looser rules). These stories are deeply rooted in Asian history, mythology, and philosophy. Expect Daoist magic, Buddhist cosmology, martial arts sects, and cultivators striving for enlightenment or immortality. From classics like Journey to the West to modern works like R.F. Kuang’s The Poppy War, Eastern fantasy is rich with qi-powered warriors, shapeshifting fox spirits, flying swords, and celestial realms.

Western Fantasy: Encompasses the medieval-inspired worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien and Brandon Sanderson, the gritty realism of grimdark authors like George R.R. Martin and Joe Abercrombie, and sprawling epic series built on prophecy and power struggles. These stories often draw from European folklore and Judeo-Christian mythology—featuring elves, dwarves, fire-breathing dragons, and archetypes like the Chosen One or the Dark Lord. From The Lord of the Rings to Mistborn to A Game of Thrones, Western fantasy explores moral dilemmas, knightly quests, and battles between good and evil.

At a glance, here are some key differences:

- Mythical Creatures: Eastern dragons are usually wingless, wise, and benevolent, while Western dragons are winged, fire-spewing, and often antagonistic. Eastern stories feature divine beasts and fox spirits; Western ones have unicorns, orcs, and faeries.

- Cultural Backdrop: Eastern settings often resemble ancient China, Japan, or Korea—with misty mountain temples and imperial courts. Western settings lean toward medieval Europe—featuring castles, feudal kingdoms, and roadside taverns.

- Magic & Powers: In Eastern fantasy, power stems from cultivating inner energy (qi) and spiritual enlightenment. Western magic often involves structured spell systems, wizard schools, or abilities tied to birthright or prophecy.

- Scope: Eastern fantasy is commonly serialized (with 1000+ chapter web novels) and follows long-term progression arcs. Western fantasy tends to focus on trilogies or contained series that build toward a singular, climactic conclusion.

A snow-covered castle perched atop a mountain evokes the classic medieval tone of Western high fantasy. Knights, dragons, and epic battles often unfold in such settings. While the distinctions above aren’t absolute—and many stories blur the lines—they offer a useful framework for comparing eastern vs western fantasy and how each tradition approaches magic, myth, and meaning.

Storytelling: Hero’s Journey vs. Cultivation Path

One of the starkest contrasts in eastern vs western fantasy lies in how stories are told. Western fantasy traditionally follows the Hero’s Journey or a three-act structure of conflict-climax-resolution. A singular hero is thrust into adventure, faces a crisis, and overcomes evil against all odds, returning transformed. This approach—rooted in ancient Greek storytelling—centers on individual agency and clear resolutions. For example, Frodo destroys the One Ring and peace returns; the story has a defined end. Western tales love a satisfying climax—even grimdark ones usually resolve the main conflict (albeit at great cost).

Eastern fantasy, by contrast, often feels more open-ended or cyclical. Many stories use a four-act structure (e.g., the Japanese kishōtenketsu) that builds tension and development without a conventional resolution. Endings may be ambiguous or bittersweet, prompting reflection. As one analysis notes, Eastern stories rarely offer a tidy “happily ever after.” Instead, they invite readers to contemplate the ongoing journey. Life is portrayed as a continuous flow, so an Eastern fantasy might conclude with the hero wandering off, having changed—but not necessarily victorious. This philosophical difference is a hallmark of eastern vs western fantasy narratives.

Another key difference is how conflict operates. Western plots are often driven by external conflict—the big villain, the war for the throne, or a doomsday prophecy. In contrast, eastern fantasy leans into internal growth and emotional tension. While there are still battles and rivalries, the story often prioritizes inner change. A cultivator’s journey might be less about defeating a dark lord and more about overcoming personal flaws or spiritual limitations. This internal focus is part of what makes eastern vs western fantasy such an interesting comparison—one prioritizes the world outside, the other, the world within.

Hero Type – Chosen vs. Self-Made: In western fantasy, it’s common to see the “Chosen One” trope—a destined hero, often of secret noble birth, who fulfills an ancient prophecy. King Arthur pulling Excalibur or Harry Potter being “the Boy Who Lived” are classic examples. In eastern fantasy, the hero is usually self-made. They begin at the bottom and climb through sheer grit, study, and spiritual cultivation. It’s the difference between being born special and becoming exceptional. This distinction is one of the most iconic traits of eastern vs western fantasy, and modern readers increasingly find value in both models.

Pacing and Length: Eastern fantasy thrives on long-term progression. With hundreds—sometimes thousands—of chapters, it follows a rhythm of challenge → training → breakthrough → repeat. Western fantasy often prefers tightly plotted arcs and payoff in each installment. Think of Mistborn or The Stormlight Archive, where each book builds toward a single climactic moment. The difference in pacing is another reflection of eastern vs western fantasy storytelling philosophies—slow burn mastery vs. moment-to-moment stakes.

Worldbuilding: Castles, Sects, and Something in Between

WESTERN WORLDS VS EASTERN TRADITIONS

Worldbuilding in Eastern and Western fantasy offers distinct aesthetics and philosophies, each captivating in its own right.

Settings: Western fantasy typically evokes a medieval European world—stone castles, lords and ladies, monster-filled forests, and adventurer-packed taverns. Detailed maps, political intrigue, and expansive geography are staples. Worlds like Middle-earth or Westeros are rich with culture, history, and continent-spanning realism.

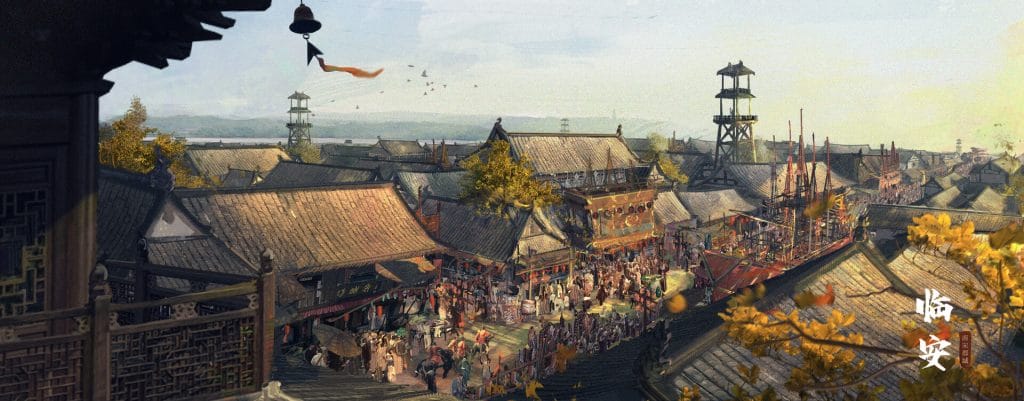

Eastern fantasy draws from East Asian mythology and history. Instead of castles, you’ll find misty mountain temples, celestial palaces, and ancient cities inspired by Imperial China. Wandering swordsmen move through the jianghu, and cultivation sects serve as schools of martial and mystical training. Spiritual realms and reincarnation cycles give Eastern settings a vertical, layered structure—earthly world below, divine realms above.

Magic Systems: Western magic ranges from soft (mysterious, undefined) to hard (rule-based). Modern authors favor structured systems, like Allomancy in Mistborn, where magic is based on ingesting metals to unlock specific powers. Western systems often focus on logic, limits, and creative problem-solving.

Eastern fantasy centers on inner energy cultivation (Qi). Instead of spellbooks, characters meditate, absorb energy, and ascend through power tiers. Cultivation involves talismans, elixirs, and mystical artifacts. Magic is earned through effort, not birthright—anyone can ascend with enough willpower. This progression mirrors spiritual growth, with powers tied to harmony, elements, or enlightenment.

Technology & Aesthetics: Western fantasy usually stays within pre-industrial limits—swords, bows, and occasionally early firearms. Eastern fantasy varies more: some stories stay rooted in mythical ancient China, while others blend steampunk or modern tech. The term “silkpunk” (coined by Ken Liu) describes this fusion of Eastern settings with fantastical inventions like silk-powered airships. Eastern worldbuilding often embraces cross-genre experimentation—time travel, otherworld portals, and dimension-hopping are common.

Example – Magical Contrast: A Western mage casts a fireball using study and birthright-limited mana. An Eastern cultivator summons a flame dragon by channeling Qi, the result of years of training and recent breakthroughs. Western power is external and gifted; Eastern power is internal and earned.

Dragons further highlight this contrast: Western dragons are dangerous beasts to slay, while Eastern dragons are wise, often guiding the hero toward enlightenment.

In summary: Western worldbuilding emphasizes political structure, geography, and external struggle. Eastern worldbuilding prioritizes spiritual progression, cosmology, and the internal journey. Many modern stories combine these approaches—offering structured epics set in mythic worlds, or introspective sagas layered over vast political landscapes

Characters: Chosen Ones vs. Self-Made Heroes

Characters are the heart of any story. Both Eastern and Western fantasy feature vibrant casts, but their heroes and tropes often differ.

Protagonists: In Western fantasy, you’ll frequently find the unlikely hero—the humble farmboy, the orphan, or the innkeeper’s daughter—destined for greatness. Examples include Luke Skywalker (farmboy to Jedi) or Rand al’Thor in The Wheel of Time (shepherd to Dragon Reborn). These characters often inherit power or responsibility through prophecy or noble lineage and grow into their roles. Traditional high fantasy tends to frame characters in clear moral terms: heroes are virtuous, villains are evil. Grimdark subverts this with morally gray figures.

Eastern fantasy protagonists typically start with nothing and earn everything through effort. They may begin as beggars, weaklings, or reincarnated nobodies, and rise through martial arts, cultivation, and countless trials—often in rags-to-riches or mortality-to-godhood arcs. Characters like Wei Wuxian from Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation or Guo Jing from Legends of the Condor Heroes exemplify this. These heroes succeed through grit, perseverance, and loyalty, though some walk ruthless paths. Anti-heroes are common, especially in xianxia, where power can blur morality.

Companions & Supporting Cast: Western fantasy often includes ensemble casts—a fellowship with diverse backgrounds and roles (mentor, comic relief, love interest). Eastern stories may focus on lone heroes, especially in cultivation tales where the protagonist advances beyond peers. If companions exist, they’re often sect brothers, disciples, or mentors. Romance appears in both traditions, though Eastern romance often involves slow burns, reincarnation, or duty-based entanglements.

Villains & Antagonists: Western fantasy frequently features a single archvillain (Dark Lord, Evil Sorcerer) as the primary threat. Eastern fantasy tends to present a series of escalating antagonists—rival clans, cultivators, or corrupt officials—rather than a singular Big Bad. Conflict can be framed in terms of karma or destiny, and today’s ally may become tomorrow’s enemy. The line between hero and villain is often blurred.

Character Arcs: Western characters often go through clear inner transformations. Vin in Mistborn evolves from a distrustful thief into a leader. Frodo, though victorious, is scarred by his journey. These arcs explore identity, temptation, and self-discovery. In Eastern fantasy, growth is usually tied to wisdom and power. A hot-headed cultivator might gain patience over centuries, or a vengeful warrior might develop compassion. Personality shifts may be subtle, with a focus on how the world changes around the character. Characters can remain morally consistent while their status evolves from mortal to divine. That said, modern Eastern fantasy increasingly explores psychological depth.

Themes & Morals in Characters: Western fantasy emphasizes free will, personal heroism, and the triumph of good over evil. Eastern fantasy often centers on fate, honor, obligation, and family. Concepts like wu wei (Daoist non-action) suggest harmony with the world, not its domination. Characters may be driven by loyalty to a master, clan feuds, or legacy. Emotional payoffs differ: Is it more satisfying to watch a cultivator finally overcome a high-born rival after 50 chapters of training, or to see a prince claim his rightful throne? Both models resonate with modern readers—and many stories today embrace both.

Themes: Fate, Power, and the Cost of Both

The tone and underlying themes of Eastern and Western fantasy have distinct flavors, shaped by the cultures from which they originate.

Mythology and Philosophy: Eastern fantasy is deeply rooted in philosophical traditions like Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. Themes of balance, cyclical time, karma, and reincarnation frequently appear. A hero might discover they are the reincarnation of a sage, or an enemy might be tied to a past life—leading to destined encounters. Power and immortality often come at a cost, with protagonists giving up ordinary lives or enduring painful sacrifices. Immortality isn’t just about eternal life but spiritual transcendence. This lends Eastern fantasy a contemplative tone, asking: What is the worth of power if one loses their humanity? What is the meaning of life if it never ends?

Western fantasy, on the other hand, draws from Norse, Greek, and Arthurian mythologies and often explores heroism, moral choices, and sacrifice for the greater good. The classic good vs. evil narrative is common, though modern stories may blur those lines. A recurring theme is hope—even in dark times, there’s usually a belief that goodness can prevail. Western tragedies often search for redemption or meaning amid loss.

Tone: Traditional Western fantasy has an optimistic tone—the hero triumphs, the kingdom is restored. Think of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe or The Return of the King. More recent grimdark fantasy leans into gritty realism, moral ambiguity, and violence, but still often includes cynical humor or introspective commentary. Eastern tones vary widely: wuxia can be melodramatic and emotional, while xianxia may be dark and brutal, built on “survival of the fittest.” Happy endings are not guaranteed; characters may suffer senselessly, reflecting a worldview where the universe isn’t always just. This can feel jarring but also honest.

Eastern fantasy often ends on a tragic or open note—the hero may fail, lose their love, or see their world remain in turmoil. This acceptance of impermanence can feel oddly comforting in its realism. Still, many Eastern fantasies are filled with humor, romance, and heroic triumphs. They simply balance joy with the idea that every victory is temporary—and there’s always a higher peak to climb.

Examples of Thematic Differences:

- The Lord of the Rings explores the corrupting nature of power and the nobility of self-sacrifice. It ends with a bittersweet peace and a message of enduring hope.

- The Poppy War trilogy tackles colonialism, vengeance, and the cost of war, ending with brutal honesty rather than heroic closure.

- Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon blends romance and action but concludes with a tragic meditation on unfulfilled love and honor’s price.

Morality: Western fantasy heroes often embody ideals like justice and courage. In wuxia, Eastern heroes may follow a personal code of xia (chivalry), while xianxia protagonists can act ruthlessly in the name of survival or revenge. Eastern morality often favors balance and perspective over binary good vs. evil. Even gods may be fallible or indifferent, unlike the clearer moral roles seen in many Western deities.

In summary: Western fantasy tends to inspire with heroism and moral clarity, while Eastern fantasy delves into philosophical questions of fate, power, and purpose. Both traditions continue to evolve—Western stories increasingly embrace moral complexity, and Eastern stories are adopting tighter narrative arcs. Many modern fantasies blend the best of both worlds.

What Readers Want in 2025

- Pacing with payoff: Not just slow burns or instant gratification—both, in balance.

- Diverse influences: Western tropes, Eastern philosophies, and fresh cultural flavors.

- Characters who earn it: No shortcuts. No destiny without effort.

- Fresh blends: Stories that borrow freely and build boldly.

Readers today are genre-literate. They’ve seen the tropes. They know the patterns. They’re not just asking, “Who wins?” They’re asking, “What does it mean to win?”

Final Thoughts (and a Small Invite)

East or West, what we’re really chasing in stories is the same: wonder, meaning, maybe even a little truth—wrapped in robes, armor, or something stranger still.

If you’ve made it this far, chances are you feel the same. So let me introduce you to the world I built with my lifelong friend, Adam—a story born from years of reading both sides of the fantasy coin, written for readers who crave a bit of both.

The book is called Asteria: A World Unbound. At its core, it follows Aaron, an assassin who dies in one world and wakes in another—a classic transmigration, but with a twist. The world he enters looks and feels Western: noble houses, broken oaths, ancient bloodlines. But the spirit of the story? Deeply Eastern.

Aaron’s journey isn’t about fate or saving the world. It’s about his own inner transformation. He’s not a chosen one, he’s a man forced to confront who he was and decide who he wants to become. Sometimes quiet. Sometimes violent. Always earned.

Our magic system reflects this blend, as well. It’s structured—Western in rules and consequences. But it’s also introspective and personal, like cultivation systems in Eastern tales. Each character’s magic evolves in unique “Circles,” tied to their choices and identity. Power doesn’t just grow—it reveals who you are becoming.

Because in Asteria, the past matters. The future beckons. And nothing is ever as simple as it seems.

So whether you love flying swords or fallen kings, dusty scrolls or ancient prophecies—this is a story that might speak to you. A story where East meets West, and something new rises between them.

Vi Mai is a writer and co-creator of the indie publishing group, Asteria Creative. He originally studied computer programming, engineering, and business in university, but quickly realized school wasn’t the path for him. After leaving school, he spent several years coaching, working in startup sales, and helping businesses—both big and small—scale through smart strategy and execution. Now, he’s finally doing what he always wanted—building a high fantasy book series alongside his best friend, Adam, set in a world that brings his creative vision to life.